Marketing Georgism

in the Culture of Contentment

Ian T.G. Lambert

[An address given at the Council of Georgist

Organizations conference,

Santa Domingo, Dominican Republic, June,

1992]

The Culture of Contentment

We live, in the age of the contented. So says John Kenneth Galbraith

in his latest book.

The Culture of Contentment[1] is one of those seminal essays

which is able to capture the state of society at a particular moment

in time and thereby start a whole new political debate. In Galbraith's

case, it is American society, but (as he points out) his observations

are equally true of the rest of the industrialised world. If, as

Georgists, we are to understand the nature of the battle in which we

are called to fight, we must appraise the nature of our adversary.

This Professor Galbraith has christened "The Culture of

Contentment". His message is clear. Post-Reagan America is now in

the grip of ah electoral majority which is supported at a relatively

comfortable level by the current politico-economic system. They are

the contented, and they will vote as an electoral block against any

encroachment on their comfortable life-style.

This culture of contentment displays a callous indifference to the

disadvantaged minority and, when drawn into debate, has the gall to

justify its position on the basis of utilitarianism -- the doctrine of

the greatest happiness of the greatest number. Utilitarianism, when

first advocated by Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, sought to

justify sacrifices demanded of the few who were rich to help the many

who were poor. Now it is the few who are poor who have to make

sacrifices to support the comparative many who are rich. Thus, have we

reached the position dreaded by Tocqueville: the Tyranny of the

Majority.

The resistance of the contented majority is not a resistance to

government as such. On the contrary, it is Big Government which

sustains them, with subsidies for rich farmers, tax cuts and reliefs

for the rich (to incentivise them), the privatisation of gains and

socialisation of losses in the banking and finance industries (through

deregulation combined with the increase of federal deposit insurance),

and an enormous military defence budget, off which countless

businesses feed.

This is the familiar culture of the gravy train, against which Henry

George himself fought. But it has changed. The numbers who have bought

into the gravy train now include a whole middle class, not merely the

industrial Robber-Barons George had to contend with. Our adversaries

are different now from a hundred years ago. A more sophisticated

armoury is displayed against us, and we must use new weapons in our

cause. So, too, this change in our adversaries means a change in our

constituency. Our supporters have changed, and must be reached in new

ways.

Why Georgism needs to be Marketed

There are two reasons why marketing is so important for Georgism.

The first is a question of efficiency. Because Georgism has a moral

message, because it seeks to remedy economic injustices, we are

sometimes confused into thinking that we do not need to be more

commercial -- "professional" might be a better term -- in

trying to get our ideas across,. We tend to confuse the virtuous with

the inefficient.

In our minds, we have to distinguish between activities which are

intrinsically not commercially viable (for example, helping the

mentally handicapped), and activities which are simply inefficiently

run. We often mistake our own inefficiency for something more virtuous

than it is. The failure of Georgism in recent years has a lot more to

do with our own inefficiency than we like to think. We prefer to think

that we have been over-run by the forces of reaction and contentment,

but in truth we have been inefficient in getting our message across.

We should riot think ourselves virtuous merely because we are

squandering our resources.

The second reason is, in the longer run, much more important.

Georgism must endeavour to live up to its own ideals. Georgism must

exemplify what it stands for, not by what it says but for what it is

and how it operates.

Georgists are passionately in favour of the free market. We all

believe in free trade. Yet, what do we do with our ideas, our policy

recommendations and our writings? We scatter them around, in the vain

hope that they will fall on fertile (rather than stony) ground. We

tend to congratulate ourselves for our "self-sacrifice", and

devotion to the cause -- for how much effort we put in for so little

return, confusing return and effect -- thereby sending a subliminal

message which runs deeply counter to Georgism's message that the

self-sacrifice demanded by socialism (and any other form of statism)

is an evil. We publish George's works with the aid of subsidies from a

charitable foundation, we seek grants, subsidies and benefits for

research. We tend to grumble that the free market will not support our

activities, so that charity must, while at the same time we spread a

message of charity for none and economic justice for all.

If we truly believe that the free market is the best way to allocate

goods, services and resources, we should commit ourselves to using the

market more to spread our ideas and our philosophy.

The success or failure of any political philosophy depends on its

ability to draw in new members. Man is an inherently social animal,

and most people will be attracted to Georgists before they are

attracted to Georgism. That is why how we run our own house is so

important. That is why marketing is so important to us.

What is Marketing?

Marketing is human activity directed to satisfying needs and wants

through exchange processes.

A market is simply a place where buyers and sellers meet to trade, to

exchange.

The lifeblood of every society is trade. It is common to all human

societies. Whatever else the Europeans brought to the Americas five

hundred years ago, they did not bring the idea of trade. Even the most

primitive peoples trade, both internally among each other and

externally with other people. To this day, the many shops across

America quaintly called "trading posts" bear witness to the

long gone days when the Indians peaceably traded with the White Man.

Everybody trades -- from the mega-rich to the homeless poor. And the

reason we do so is because we all gain from it. In free exchange, each

party gives up what he values less in return for what he values more.

Each party gains. Each party wins, and there are no losers. Nobody is

made to sacrifice that others may gain.

Now, all markets are consumer-led. It is the consumer who goes to the

market to obtain what he wants. It is his demand that causes producers

to produce and supply.

Marketing involves many things within an organisation, but its goal

is always the satisfaction of consumer demand. During this century,

Georgism has gradually lost touch with its market, because its

consumers have changed. We know that our adversaries have changed, but

we do not always realise that this means that our constituency - our

consumers - has also changed. There is a whole new generation waiting

to hear our message, if only we can reach them.

Georgism's Goal

Some of you may have heard of Robert Townsend, former CEO of Avis

Rent-A-Car, author of "Up the Organisation" and now business

consultant. In Bob Townsend's view, every organisation should have a

stated business goal which is known to everyone in the organisation

and which helps to focus their efforts. This has to be simple, so

simple that you do not have to write it down to remember it. At Avis,

it took them about six months to hone down their business goal to

simply this: the renting of vehicles without drivers to customers. It

has to be that simple.

Such an organisational goal must not be confused with higher and more

generalised objectives, such as: satisfying our customers; making

money; keeping a loyal and happy workforce. Such stated objectives do

not focus our efforts. They tell us what we know already, without

indicating how we are seeking to achieve it. Nobody ever set up a

business simply to "make money" -- other than a

counterfeiter!

Likewise, as Georgists we must not confuse our ultimate aspirations

with our organisational or political goals. Of course, we want to

achieve liberty, justice and peace; but these are not Georgism's

organisational goals. They do not focus our efforts. So what are?

When I first thought about this, I saw Georgism as having twin goals:

land value taxation and the free market. But to say that we have twin

goals seems to imply either that they are independent or that some

sort of trade-off or compromise between them may be needed. This is

one of our great mistakes. We do not have twin goals, but a single

goal with two elements. Land value taxation and the free market are

two sides of the same coin. You cannot have a truly free market

without land value taxation, for private property in land is the

mother of all other monopolies. You cannot have a free market unless

government abolishes all taxes which fall on production. Equally, you

cannot have a proper system of land value taxation without a free

market -- as Georgists who have visited Russia and Estonia have tried

to get across -- because LVT is a tax according to the market rental

value of land. If there is no real market, determining the "rent"

of land becomes an arbitrary function performed by the state.

Packaging Georqism

While this may be our organisational goal, we have to remember that a

product has to be packaged to be sold. It is a mistake to think that

your organisational goals will also serve as a name or description for

your product. Bob Townsend's company was not called: "The Renting

of Vehicles to Customers Corporation" for good reason. First,

such a name has no appeal (other than a purely intellectual one); and

secondly, it doesn't distinguish the corporation from any other

company in the same field or business.

Brand names are crucially important; but they do not have an

intellectual origin. They are devised not for their conscious mental

appeal, but for their subconscious appeal. Names such as "Fairy

Liquid" and "Coca-Cola" are new language created by

businesses and the meaning of which is likewise created by them - by

association.

The implications for Georgism are clear. In terms of our goal, of

land value taxation and the free market, whatever the movement chooses

to call itself may be irrelevant. It does not have to be, for example,

"The International Union for Land Value Taxation and Free Trade".

It is what people associate with the name that really counts.

The recent agonising over a name for our movement has been the cause

of much dissipation of individual energies. Whether it be "Geocracy",

"Geonomics", or just plain "Georgism" what matters

is not how the name sounds to us, but what the public come to

associate with that name. For example, "Liberalism" today is

a very different political philosophy from a hundred years ago, but

that is of little consequence today. What matters is whether or not

the "public associate anything definite with the term "Liberalism";

in Britain, they clearly no longer do.

We must ensure that the public know what we stand for: land value

taxation and_ the free market; and that they associate our name with

that policy.

Who is the Georqist Consumer?

If we are to market Georgism successfully, we must know what its

market is -- who its consumers are. To borrow a phrase from John

Burger, we must go after prospects not suspects. It is easy for us to

identify who will be opposed to our ideas and policies -- the vested

interests of the culture of contentment. It is more difficult for us

to focus on precisely whom Georgism will appeal to; but it is a

vitally important task for us.

I have thought hard about the qualities we should look for in a

prospective Georgist. it seems to me that the following are essential:

- that he (or she) is disaffected with current politics, and

current economics;

- that he is , to a greater or lesser extent, an individualist,

and not a collectivist;

- that he likes to think for himself and is not afraid of holding

unpopular or controversial views, if he truly believes in them;

- that he believes, whether vaguely or clearly, in the idea of

social and economic justice; and

- that he believes that the answers to our social and economic

problems lie somewhere beyond capitalism and socialism.

These seem to me to be the essentials. Anyone having these qualities

is a potential Georgist (a prospect not a suspect), and it is our

responsibility to make him a committed Georgist.

In terms of well-known personalities, there are many whose support we

should seek. Recently, four have come to my mind: first is Robert

Nozick, the author of Anarchy, State and Utopia, which in the

1970's was the fountainhead of modern libertarianism. He has publicly

acknowledged that he no longer holds the views expressed in his

earlier work. He has been afflicted with a social conscience, and

thinks his earlier views must be modified, but he is not entirely sure

how. (Doubt is one of our greatest assets.)

The second is Noam Chomsky, heralded by many as the intellectual

leader of the Left in America. He is fiercely anti-statist and

anti-nationalist. At one time, he described himself as an "anarchist

socialist", which is something of a contradiction in terms. Here

is a figure fumbling for a political creed that combines liberty and

social justice, freedom from poverty and freedom from state

intervention. Here again is someone looking for a third way, something

new.

The third is a British businesswoman, Anita Roddick, founder of The

Body Shop retail group. She is someone committed to environmentally

friendly free enterprise, to new ideas, to a free and fair society, to

a new political philosophy. She is passionately interested in peace

between nations and environmental issues. Here again is someone who is

certainly not socialist, who has experienced capitalism as an

entrepreneur and has significant misgivings, who is searching for

something new.

The fourth is the film actor Martin Sheen, whose commitment to

helping the homeless (particularly of Southern California) is well

known. He recently played a guest cameo role as a vagrant in a film

drama about a fight to keep a homeless shelter: "Original Intent".

Here again is a new prospect for us.

Such people are, in my view, all potential Georgists; but to win them

over, we have to show that Georgism is a rich and diverse philosophy

extending far beyond local tax reform in a few American cities -- a

whole new approach to political and social problems.

Apart from such individuals, who can give us a higher profile,

credibility and financial support, there are also interest groups for

whom Georgism has so much to offer. The following come to my mind:

- local governments, not wedded to party politics, but interested

in practical measures, such as tax reform; we know of the great

work that Steve Cord continues to carry on in towns and cities in

America, particularly Pennsylvania;

- national governments which have abandoned their previous

ideology, and who have significant misgivings about both

capitalism and socialism; the former soviet states are ripe for

conversion to Georgism, and many Georgists are playing an active

role there;

- the coloured population of America; their struggle continues;

they have seen the abolition of slavery in the nineteenth century

and the abolition of segregation in the 1950's; we must show them

that their next step on the road to liberty and justice is to

champion the human rights of all to access to land;

- the young, particularly those who are unable or only barely

able to afford to buy their own homes; even though they are far

better qualified than their parents and grandparents;

- environmental groups of all kinds; the Green Party in Britain

was decimated in the recent general election, partly beqause those

in the culture of contentment voted en bloc for conservatism but

mainly because, in the greatest depression for sixty years, they

had no credible economic policies. We have to be selective here;

many environmentalists tend to extreme authoritarianism in

economic matters; such fanatics are often not worth talking to;

but there are many environmentalists (Anita Roddick for one) who

want to preserve a responsible free market and who see governments

as a large part of the problem -- the Soviet Union had an

appalling environmental record.

We must narrow our focus and talk to people who are genuinely

interested in hearing us; the culture of contentment will only delight

in wasting our time and dissipating our resources.

We Need to Listen More

Jean Paul Sartre said that most conversations are merely competing

monologues!

A major difficulty we have as Georgists is that our whole frame of

reference is different from most people's. It is hard for us to have a

sensible conversation with economists, for example, without first

clarifying the sense in which we use terms such as "capital"

and "rent". However, most attempts to create a new frame of

reference for people are dismissed as attempts at ideological

indoctrination. With the demise of the Cold War, we live in a highly

unideological world. Therefore, rather than impose a point of view on

others, we must help people to undermine their own and to reconstruct

it.

Our greatest asset is doubt - the doubt of other people. The

psychiatric profession tell us that it is impossible to cure a patient

who will not admit that he is ill. There is no point in our talking to

those who are certain they the answers. Georgists far too often serve

up the solution and then ask what the problem is. It is only when

people will admit that they have a problem, which their philosophy,

their economics, their political theory or their religion has no

answer to, that we can really break through.

To do this, we have to let people speak for themselves. One of the

psychoanalyst's great skills is to refrain from talking. As a patient

talks arid pauses, the ensuing silence encourages him to talk further,

to work things out for himself. So must we help people think things

through for themselves. There are many different levels of

understanding. We must get people to understand Georgism at some

level. Appeals to blind faith or simply to "put your trust in us"

may have some success initially, but the real strength of Georgism is

not the integrity of Georgists, but its merits as a rational system of

political economy.

We need to listen a lot more. As I said in my presentation at the

Santa Fe conference two years ago, in the words of Lao-Tsu: "The

journey of a thousand miles starts with one step". We must take

that step towards the public and listen to them.

We need to Keep our Message Simple

In marketing we have an approach called the "KISS"

philosophy - Keep It Simple, Stupdi. The greater the complexity, the

fewer the people you reach and the lesser the impact you have.

Georgism is an essentially simple philosophy. Anyone can understand

it. We must make it clear that, while we have a lot to say and to

contribute, it is not because Georgism is long and complicated, but

because we have a lot of simple things to say on many different

subjects.

The power of the Georgist programme lies in combining essentially

simple ideas: the free market and land value taxation.

We need to Communicate more Effectively

We live in an age of audio-visual imagery. It is very different from

Henry George's day. There have been immense technological changes in

the media, which have not only altered the way we communicate; they

have altered the way we think.

In George's day, there was no radio, television, video or cinema. If

you were informed at all, you had to be able to read continuous prose,

and this accounts for the astonishingly high literacy rate,

particularly in America[2]. Nowadays, few people need to be able to

read well to be kept informed of current affairs. The radio,

television, video, or cinema all inform him with much greater

intensity, and with much less effort on his part, than books,

newspapers or magazines.

People sometimes point to the tremendous growth in sales of

newspapers and magazines as a sign that we are becoming more literate;

but all our newspapers and magazines acknowledge, in their very form,

the supremacy of imagery over abstract thought. A

Times reader of even sixty years ago would have been

astonished to find photographs in his newspaper, let alone the colour

ones we have today. But few magazines and newspapers sell today

without photographs, cartoons, graphics and imagery of every

description.

Likewise, following the inventions of the telephone, and mass

transportation, few people today need to be able to write continuous

prose to be able to communicate effectively.

This change in our media of communication has also radically changed

public discourse, particuiarly in politics. Audio-visual images

communicate with greater intensity, but also with less breadth. It

simply is not possible on radio and television to communicate with the

same detail as it is in the printed word. For one thing, all audio and

audio-visual communications must proceed at the pace of the slowest

listener or viewer. When you read a newspaper, you can read at your

own pace and flick back and forth; but when you are listening to the

radio or watching television, you have to take in what is being said

at the pace it is being given out. Books and newspapers are therefore

a very private medium of communication, radio and television a very

public one.

Political philosophies are now marketed like coca-cola, with images,

slogans and bite-size statements of policy goals. If Georgism is to

communicate effectively, it must be prepared to simplify its message.

This change in communications means we must move on from George's

works of continuous prose -- which many people today, alas, find

difficult to read -- to more effective communications, using modern

technology: graphics, imagery, cassette and video tape. And let me be

the first to acknowledge my sins in this respect; for I have long

produced learned works of prose in the Georgist cause. They have their

place in the fight for intellectual credibility, but they will not

reach a mass audience.

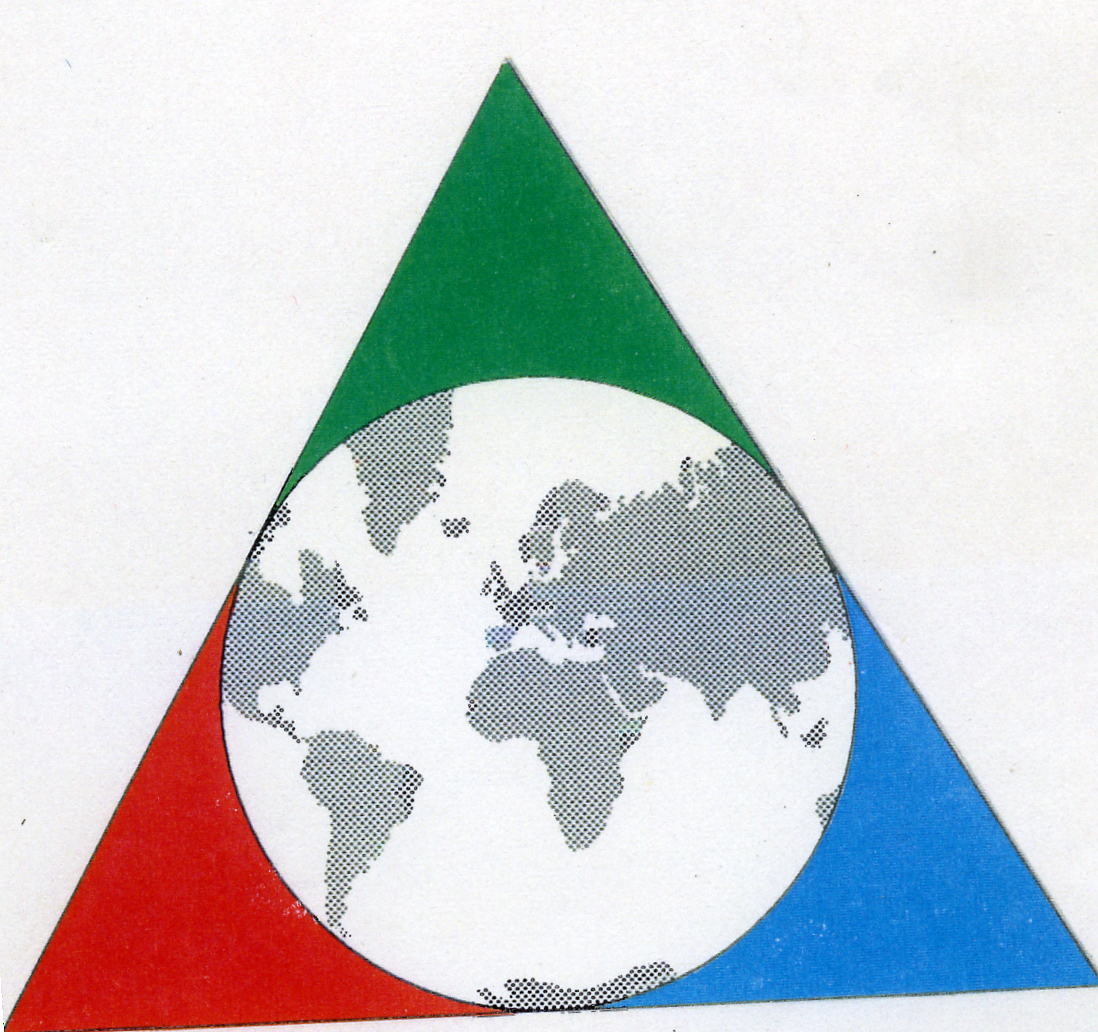

That is why, last year, inspired by Gill, Icreated a greetings card

incorporating a Georgist symbol. It appears (in black and white) on

the cover of this paper.

The symbol is a triangle, with the globe inside. The left-sector is

coloured red, representing the red of left-wing politics -- of

socialism. The right sector is coloured blue, representing the blue of

right-wing politics -- of conservatism. The third sector is coloured

green -- representing the green of environmental politics -- not left

nor right, but out front. The circle at the centre is white, the

colour which you get when you combine red, blue and green light. It is

the colour of peace. It represents the Georgist philosophy, at the

heart of events, uniting the extremist and errant philosophies of

socialism, conservatism and environmentalist. The circle represents a

perfect figure -- the ideal society -- and encompasses the globe,

emphasising that Georgism is an international philosophy. The

three-sided triangle emphasises that Georgism is a three-dimensional

philosophy, a philosophy which takes us up into the third dimension,

above the flat earth of two-dimensional politics which our society

currently moves in. The triangle also symbolises Georgism's emphasis

on the three factors of production: labour (red), capital (blue) and

land (green).

Above the symbol, there are the three hedings: "Peace, Harmony

and Economic Justice", which are our ultimate objectives.

The experience has been very interesting. The cards have had much

greater impact than my papers, because they are simple, and graphic.

They capture the fact that Georgism is new, that it is holistic, and,

most of all, that we have to look at things in a new way.

I guarantee that, long after you have forgotten my presentation

today, you will remember that symbol.

It is thus that, we must communicate.

We Heed to Trade Ideas

I was going to say we need, to "synthesize", but that

sounds too complicated. We need to trade ideas. Georgism has a huge

amount to offer other people, in economics, in politics, in sociology,

in religion. But they also have things to offer us. Marketing involves

exchange, and we must be prepared to exchange ideas with others.

There are several reasons for this. Most important of all is the fact

that, if we are to make any political progress, we must work with

others, seemingly of a different persuasion. We all know that tyrants

keep their control over a people by dividing and ruling. We all know

that such a people must unite to conquer. So must we. Our adversaries

delight in distinguishing us from their political movements and we

seem to enjoy being different. This is a tragedy. Progress for us

involves uniting up with others, not breaking down into smaller and

smaller highly differentiated groups.

As an intellectual process, it is very easy to analyse, to break

things up into their components. So dominant has analysis become that

some philosophers maintain that philosophy is just analysis! But the

great hallmark of man is not his ability to distinguish between

things, but to discern that which is common to several things which

are different. This is how we formulate concepts in our minds, from

various different perceptions. It is only by such a process that

something like philosophy can even exist.

In exactly the same way, it is a highly important task for us to

identify the elements of other political philosophies which are common

to our own, whether it be 1ibertariariism, environmentalism,

conservatism or socialism. It is only from a common ground of shared

values and ideas that we can make any progress at all.

This does not involve compromising our principles, abandoning our

commitments to land value taxation and fee trade. It involves filling

the gaps in and building on our philosophy.

During this year, I have been to three other conferences. In Rio de

Janeiro, I attended the Congress of Political Economists' conference.

They are committed to evolving a concept of "economic democracy".

There was tremendous interest in Henry George. In April Gill and I

attended the British Deming Association conference in Birmingham

(England). The ideas of W. Edward Deming in the field of business

management are very important for us. Henry George had no particular

theory or philosophy of management of the individual enterprise.

Deming's ideas supplement his ideas in political economy. Equally, I

am convinced that Georgism is very important for the long term success

of Deming's ideas in the west. Deming's philosophy is radical, and it

will really only work when operating throughout society. Deming needs

a politico-economic philosophy to ensure the success of ideas at the

management level.

Finally, I attended the Ludwig Von Mises Institute conference at

Jekyll Island, Georgia, on the subject of the Federal Reserve System.

Austrian economics has a lot to offer Georgism, and Georgism has a lot

to offer it. If Georgism is to be a credible economic philosophy, it

must develop a sound understanding of our monetary problems and

advocate credible solutions. Since George's day money has effectively

been nationalised and has become entirely subjective, following the

abandonment of the gold standard.

I am convinced that Georgism needs to follow a programme of active

synthesis, tying itself into ideas in other fields. My recent paper,

called "Out of the Crisis with Deming, George and Mises" is

an attempt in this direction.

We must create a free market world of ideas, in which people can move

freely and exchange ideas. We must exemplify our belief that there is

no property in truth, knowledge or wisdom. We must help to break the

protectionist mentality of our own and other movements, that

constantly seeks to separate and isolate. Between protectionist blocks

there can never be true dialogue, only competing monologues and

eventual war.

Let us never forget that whenever two people are quarrelling, a third

person is usually quietly benefiting at their expense.

Success is Failure turned Inside-Out

Our greatest opportunity lies with those who have failed and who will

admit to their failure. W. Edwards Deming was able to help turn around

Japanese industry, because Japan was in a crisis. They knew they had

to change. They were willing to risk -- they had nothing to lose --

and they sought out Deming. Ironically, Deming tried to sell his ideas

to American industry for thirty years, without success, before turning

to help Japan. Today his portrait hangs in the foyer of Toyota's

headquarters in Tokyo, as a tribute to the American who taught them

all about quality.

Success is failure turned inside out. The psychiatric patient who

subscribes for therapy is already half way to being cured. Admitting

failure is the start of recovery. That is why a great opportunity lies

for us in the former Soviet Union.

It is also why our task is so much more difficult in America, where

the demise of communism is seen as a vindication of capitalism with

all its faults.

What Return can we Make?

Marketing involves trade. We must use our ability to trade more . The

whole essence of trade is free exchange. When we are marketing our

ideas and policies, we should be prepared to ask for something in

return. It may be money, but it does not have to be.

We should be prepared to charge at commercial rates for consultancy

advice, for example, to local and national governments. We should

approach the matter commercially. If we want to sell the power of our

ideas to them, we can give a credit for the first however many hours

of advice. Given out confidence in the power of Georgist ideas, we

should also be prepared to charge fees according to results, for

example, cost savings or economic growth.

The pricing of goods and services is not a science; it is an art. One

of the curious truths of marketing is that goods and services which

are lowly priced are not greatly valued by the consumer. Somehow,

charging more makes people think that what they are getting is worth

more. This is very important for us. Our courses at schools and in

correspondence are priced far too lowly. Charging more will enable us

to improve the quality of the printing, publishing and teaching. That

is important because it has truly been said that you never get a

second chance to make a first impression.

We realise that many of our students could find it difficult to

afford courses and materials. The solution to this is not to reduce

prices but to give discount vouchers. A person who is unemployed can

be given a $75.00 discount voucher for a $100.00 course. If you do

that, he will believe that he is getting $100.00 of value. Moreover,

the wealthier person, whose cost of doing a course is not money but

time - his opportunity cost -- will have no difficulty in paying

$100.00, $200.00 or even $300.00. In fact he is much more likely to

take the course if it costs that much, than if it costs only $25.00,

because time is his most valuable commodity.

Similarly, if we want to encourage people to take all 3 or 4 courses,

we can give them a credit voucher at the end of the first course,

entitling them to a discount on the cost of the next next course if

they enroll within, say, 60 days. We can offer students on the course

the opportunity of introducing the course to others and, if they

enroll, obtain a discount voucher from other courses, or to buy books

(I am sure an arrangement with the Robert Schalkenbach Foundation can

be reached). At the completion of the courses, we can offer a discount

voucher on the cost of attending the next CGO conference. In this way,

we can coax people from enrolling on their first course to eventually

becoming active Georgists.

But we should also consider consideration other than money or money's

worth. If we have unemployed students, their scarce resource is money,

their abundant resource is time. We must make use of their time.

This will not only help us. It will help individuals to play their

part. Nearly every Georgist convert I meet wants to do more, and is

frustrated that he cannot.

What can the Individual do?

There are many Georgists, and I am one, who are isolated Georgists.

We have no schools, associations or groups to attend, to meet friends

and exchange ideas. But, though isolated, we are not solitary. We can

communicate with other Georgists, by post and fax, in journals and at

conferences such as this one.

I see the task of such isolated Georgists as being to recruit new

members. In a democracy, political action, even legitimacy, comes

through strength of numbers. As I travel round, I have come to think

of myself as an evangelist -- literally, a bringer of the good news.

Here are some ideas for what an isolated Georgist can do:

- When you go to stay with people now, rather than buy them

chocolates as a gift, you can bring a copy of the abridged version

of Progress and Poverty or the new paperback version of

Protection or Free Trade.

- For some people who are good friends and influential in their

field, you can pay for an additional subscription of "Land

and Liberty" -- I think it costs just £2.00 per annum

for an additional subscriber. Not only does this keep up the

communication of Georgist ideas, it increases the circulation,

which is very important (for example) in generating advertising.

- You can encourage friends and others to take the Henry George

Institute correspondence courses, run by Bob Clancy. They are an

excellent introduction to Georgist economics.

- With the help of the Robert Schalkenbach Foundation, you can

donate copies of George's works to libraries, at colleges and

publicly. (Earlier this year, with the help of Oscar, we managed

to donate a complete set of George's works to the International

College of the Cayman Islands).

- As you now know, we have generated a Georgist greetings card --

actually, it had its generation in my frustration that we did not

seem to have a Georgist Christmas card.

- I also write articles, usually in an attempt, to open up

communication with others in other fields or institutions -- from

the Deming Association, to the Mises Institute, to the Congress of

Political Economists to the Institute of Taxation.

- People often do not like having to pay for papers or articles,

even when the money is ploughed back into the organisation. Such

money is often only used to print more copies. So I have now taken

to asking a new price for some of my papers or articles. It is

this:

"If you have enjoyed reading this article, we

should like something in return. Our price is this. Please make

two photocopies of this article and pass them on to people who

you think may be interested, together with this same message. In

this way you can repay us and help us to spread our ideas. Thank

you."

This is an important way of spreading our ideas, and generating a

new "sales team" of Georgists.

These are just some of the ways you can help, on your own.

Conclusion: Westward look! The land is bright.

We are faced today with the powerful inertia of the culture of

contentment. It is this, not socialism, which is our current

adversary.

To overcome that inertia, we need to become more professional in how

we spread our ideas and our philosophy. We need to market Georgism. We

need to go after prospects, not suspects.

Most importantly of all, we need to be persistent. We must follow up

our contacts, follow through with our ideas. We are starting to make

visible progress in Russia, Estonia and South Africa. Over years of

battle, we have made terrific progress in Pennsylvania.

It can take many years of laying the ground to be able to break

through. When you build a new building, you start with plans and

calculations. You have to lay the foundations. People passing by the

site may see no visible progress, but that does not mean that progress

is not being made. Very soon they will be surprised to find a building

there.

When people talk to me, depressed at how little progress we seem to

be making, I like to quote them these lines of Arthur Hugh Clough:

And while the tired waves vainly breaking

Seem here no painful inch to gain,

Far back, in creeks and inlets making,

Comes silent flooding in the main,

And not by eastern windows only,

When daylight comes, comes in the light

In front the sun climbs slow, how slowly

But westward, look! The land is bright.

|