A Cityless and Countryless World

An Outline of Practical Co-Operative Individualism

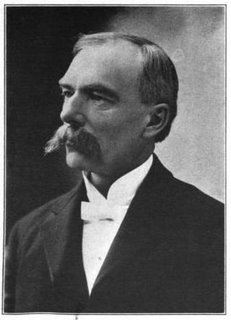

Henry Olerich

[A condensed and edited version of the book

originally published

by Gilmore & Olerich, Holstein, Iowa, 1893 / Introduction]

What follows is the edited and condensed text

of Henry Olerich's remarkable case for the transformation of

societies under principles of cooperative individualism, as he

defined this term. In the original text, Olerich uses the

vehicle of a visitor from another, more advanced planet,

interviewed on earth, who describes the how beings on his planet

solved the socio-political problems that continued to plague the

people of earth. I have edited the text to remove the narrative

while retaining Olerich's essential points. The reader is

directed to the original version to experience the full dramatic

effect of the author's presentation. [Edward J. Dodson - August,

2007]

|

ONE who is not totally blind and insensible to our present conditions

and to the passing events, can see at a glance that mankind in nearly

all its activities is still harassed by detestable friction. It is

true that we have made wonderful achievements in our so-called

sciences. Intelligence as a whole has ever broadened and deepened. We

have photographed stars too remote to be seen even with the most

powerful telescopes. We have weighed the planets and have ascertained

their distances. We have ascended into the clouds beyond the reach of

the naked eye. We have explored the bottom of the sea and have

examined the deep strata of the earth s crust. Our cities are

illuminated with a continuous flash of lightning. Architectural skill

has erected colossal structures which it has splendidly finished and

gorgeously decorated with the hand of art. By the telegraph and

telephone we have almost annihilated time and space. In the phonograph

we have impressed a voice on the mineral kingdom. On the floating

palace of the ocean we can, in a few days, migrate from one continent

to the other. We journey in comfortable, speedy trains. Wonderful

agricultural implements till the soil. Manufacturing and mining have

developed to gigantic industries. The expansive force of steam and the

electric current turn our ponderous wheels of toil. Everywhere

progress is visible. The food, clothing, shelter and luxuries of the

masses are, no doubt, better now than they were ever before in the

history of the human race. Mental activity is bolder, broader and

freer. Fights, quarrels, paternalism and monopoly are gradually

diminishing.

But notwithstanding all this, there is still room for vast

improvement; and one who has the real interest of himself and

companions at heart will not close his eyes against existing evils. He

will boldly and fearlessly face them, and endeavor to diminish them by

a diffusion of a higher and wider intelligence.

A thoughtful observer can not wend his way in any direction but what

he is still confronted by abominable evils which are still preying on

the purity, well-being and happiness of mankind.

In our cities we meet countless men, women and children with pale

faces, who are starving for want of sunshine, pure air and out-door

exercise. Thousands of industrious persons are forced idlers.

Thousands are living in hovels and garrets unfit for a human abode.

Thousands are paupers and tramps. A countless army of men, women and

children are mere machines, working a long, toilsome day in a mill,

factory, or workshop. A large class of women, in order to make a

livelihood, are selling themselves into marriage, or for other vile

purposes. Our farmers are largely spending their lives in country

solitudes, toiling principally for the capitalist and landlord.

A vast multitude, in fact nearly all of our so-called laborers, are

toiling so hard and so long daily, for their mere material subsistence

that little, if any, energy is left for personal cleanliness and

mental culture. Our land tenure monopolizes the earth's surface. Our

medium of exchange which is rapidly concentrating wealth offers

special privileges to the rich. Our system of education is largely

cruel, unnatural and otherwise injurious. Husband and wife, parent and

child, often quarrel and fight and sometimes kill each other and

commit suicide.

Our government is largely invasive and despotic, and principally run

by politicians, who are grossly ignorant of the psychological

principles of human nature. Children, on the one hand, are neglected

and starving, both physically and mentally; and, on the other hand,

they are tyrants and little more than grown-up babies. Care and sorrow

are stamped upon nearly every brow one meets. Mothers, as a rule, are

maternal slaves, feeble and care-worn. Strife, revenge and jealousy

are absorbing a large share of our best energies. Much of our labor is

unproductive and destructive, and most of our machinery, tools and

means of transportation are manipulated in the interest of the rich.

Paternalism stunts individuality, and monopoly prevents the masses

from becoming prosperous.

It is a well-known fact that a stupid, ignorant person, unlike an

intelligent one, can bear most any burden without being galled by it.

Hence all our present agitations, dissatisfactions and utterances of

discontent are only so many tongues that are beginning to speak by the

force of a rising intelligence and an increasing sensibility, which

causes the victims slowly to become conscious of their unjust burdens.

It is, no doubt, true that, as a whole, we have been and are still

gradually marching toward individual freedom and equity, but, as. we

have seen, are still far from having attained them. Some of us have at

last learned that happiness of self includes the happiness of others,

and that our conscious efforts, guided by the highest intelligence,

may be made to count in promo ting this progressive march. For these

reasons I have concluded to contribute my infinitesimal part of this

conscious work of progress by outlining, in these printed pages, a

social and economic system from which, I believe, our existing evils

are eliminated; and to still further assist in this labor, I compare

this new system with our present one, so as to make the work more

perspicuous for those who are not much accustomed to think for

themselves. I also name and describe some of the successive steps of

progress which slowly succeeded one another.

In this work I shall further endeavor to show that social and

economic prosperity and harmony can be attained only in a system which

recognizes extensive voluntary co-operation as its fundamental

principle of production and distribution, and which concedes to every

individual the right to do as he wills, provided he does not infringe

the equal right of any other person; for in the harmonious and

intelligent union of these two factors consists the solution of the

social and economic problem.

I am well aware that my work will meet with strong opposition from my

timid contemporaries. I am aware that they will endeavor to spread the

alarm that this book is dangerous, but such a course is nothing new

and nothing strange. Persons whose hearts are cold and full of

iniquity have never been able to see and feel beyond the very limited

sphere of their own activity They measure all other people by their

own crude and wicked intentions. Cruelty and blind zeal have always

led such persons on unwise paths. Countless examples may be cited in

support of this proposition.

Socrates was accused of corrupting the youth, and was, therefore,

condemned to drink the poisonous hemlock. Jesus, who advocated nobler

and purer principles than His contemporaries, was crucified by them.

Washington, who believed in a republic which concedes a little more

individual freedom than a monarchy does, was branded a traitor by his

monarchical contemporaries. Garrison, who advocated the liberation of

chattel slaves, was denounced a dangerous demagogue. When Luther added

a degree of personal liberty to the inflexible creed of his time, all

Christendom branded him a heretic; a subverter of human well-being.

Haeckel, Huxley, Spencer, Darwin, Bucket, Pentecost, Tucker and

countless others, who have vastly enriched the storehouse of human

knowledge by their genius and industry, have all, in their turn, been

calumniated and denounced by persons who have, perhaps, never read a

line of what these leading men have written.

I do not make these remarks concerning criticism on the ground that I

fear that my work will not bear analysis and examination; but, on the

contrary, I kindly invite the keenest critics to subject the contents

of it to the closest scrutiny. I am keenly conscious that this book,

like all others that have ever been written, contains errors and

shortcomings. To assert the contrary implies perfection, and no person

who is ordinarily well-informed will claim to be perfect or

infallible; but I can afford to invite criticism, for I shall be as

much interested in having my errors and shortcomings pointed out as my

critics are, for I have no creed, no party and no organization to

defend, but am merely searching for truth, and truth needs no other

defense than that of discovering it.

Now let me state right here that I do not wish to be understood that

the masses, who are now living, are suited, as they are at present

constituted, to enjoy and become members of a social and economic

system as pure, high and noble as the one rudely outlined in this

work; but the aim of this work is to fit that vast multitude who are

still unfit for it by having them mentally assimilate some of the

facts expressed and suggested in it, for let us not forget that

man-made institutions are, as a whole, always nearly suited to the

mental capacity of the masses. A comparison of the minds and

institutions of the savage with those of the more developed will

substantiate this great principle. Improve the mind by unfolding it,

and the human-made institutions will improve to correspond.

Let me here advise the reader not to omit any chapter or read them in

any other order than the one given in the book. It is not a fact, as

many believe, that a single topic can be successfully learned or

discussed without having it closely connected with others. For

examples, a change in a locomotive implies or produces a change in the

roadbed, in commerce, in speed, in mercantile business. A change in

the land tenure and in the medium of exchange produces corresponding

changes in all other human institutions and conduct; if not, one land

tenure and medium of exchange would be as good as another. A change in

sex-relations is accompanied with a corresponding change in dress,

food, dwellings, education, modes of travel, amusements, individual

freedom, in the manner of rearing offspring, and in countless other

ways. A system, in order to be natural and harmonious, must be a

connected whole. Hence we can see at once that the very act of

endeavoring to learn or discuss a single topic unconnected with others

is a sign of mental incompleteness.

With these prefatory remarks, I humbly submit the following pages to

the thoughtful consideration and impartial judgment of a continuously

progressing individual.

CONTENTS

|